Archive

In a Pig’s Eye

On April 8, 1642, the gallows of New Haven Colony swung for George Spencer, servant and all-around reprobate, if the records of the General Court are to be believed. On the same day, Spencer’s accomplice, as unwitting as she might have been – though Spencer said she, with her beguiling eyes and a touch of evil upon her, tempted him beyond self-control – also faced the ultimate punishment for her part in the crime. An unnamed executioner ran her through with a sword as Spencer watched, his former lover slaughtered, much to the community’s approval.

Who was Spencer’s unfortunate lover and partner in crime? A sow that farmer John Wakeman had recently bought from Henry Browning, Spencer’s master.

Yes, a sow.

A pig.

Oink.

The crime, of course, should be clear. But if it’s not, consider the evidence that gave away Spencer’s guilt, at least in the mind of his Puritan neighbors. Spencer had only one good eye; in the other socket, a milky false device called a pearl filled the hole. And his partner, the sow, had months before given birth to piglets. One of them, a “monster” to the colony’s officials, had just one eye – a cloudy, grayish mass just like Spencer’s pearl!

I first came across the bestiality of George Spencer in a footnote. I’m doing research for a book on capital punishment – a historical overview, with arguments for and against. Of course, until the Enlightenment (as I wrote here earlier at the The History Nerd), not many people spoke out against the death penalty. After all, it has been public sport and spectacle since at least the Romans, and widely practiced for centuries before them. Whether seen as vengeance, deterrent, or a communal balancing of karma, the death penalty has long been a popular form of punishment.

And a scant three or so miles from where I write this, few excelled at killing the guilty like the Puritans of New Haven, along with their spiritual brethren across New England. Of course, as was often the case in Europe, just because capital offenses were on the books, not everyone found guilty shook hands with the hangman (an allusion to perhaps the greatest anti-death penalty song of all time.) Still, you look at the law codes of New England and the list of capital crimes is long, most taken from the Mosaic law of the Old Testament. Some examples: adultery, witchcraft, blasphemy, sodomy, certain crimes against property, and of course, George Spencer’s barnyard recreation.

Knowing what I did about the New Haven Puritans, I wasn’t surprised that he died for his crime. But I was intrigued to learn more about him. Thankfully, the early records of the colony are online, and they provide more details about him and his abominable offspring.

It seems a few years before, Spencer started his life of crime when he tried to rouse some other servants to steal a boat and sail to Virginia. (The vessel – you can’t make this stuff up, folks – was called the Cock.) He was whipped and sent out of the plantation, but evidently found his way back and came under Henry Browning‘s roof (most likely he was Browning’s indentured servant).

Early in 1641, the Wakemans noticed something odd as they examined the piglets borne by the sow they had recently bought from Browning. In addition to the telltale Cyclopsean eye noted above, the animal was hairless, with reddish white skin like a child‘s. And above that single eye – a detail I did not see described in the secondary sources – “a thing of flesh grew forth and hung down, it was hollow, and like a man‘s instrument of generation.” If that‘s not a sign of devilish interspecies coupling, I don’t know what is!

Forced to confront the monster and the similarity of its deformity and his (the eye: I‘m not suggesting George also had a a man‘s instrument of generation dangling from his forehead), Spencer admitted his guilt. But then recanted. Then admitted, and back and forth. At one point, he said the sow came to him while he worked, after “the temptation had been upon his spirit” for several days. Then after sunset, he took her in the sty, sealing his fate.

Reading the records, it seems Spencer’s playing fast and loose with the truth and his general unChristian demeanor bugged (hmm, bad choice of words?) the Puritan fathers almost as much as the crime itself. They accused him of mocking God, after he put up a broadside asking the community to pray for him, then denying his original confession. The court found him guilty, though Spencer languished in prison for months before the sentence was carried out.

The time spent contemplating his mortality seemed to soften the former profaner and “abettor of others to sin”; at the gallows, he told some youth present “to take warning by his example.” Yet Ol’ George still had some fight in him too, as he tried to blame a sawyer named Harding for giving him bad counsel – namely to recant his first confession. Harding denied it. Then the sow was slain, and with the rope around his neck, Spencer seemed to find God at last: “God opening his mouth before his death, to give him the glory of his righteousness, to the full satisfaction of all then present.”

Spencer’s case was part of what historian John Murrin called “the bestiality panic of 1641-43.” Another case came after the panic passed, again in New Haven. And again, portents too strong to ignore seemed to point out another soul guilty of consorting with a sow. Not only did one of two deformed piglets from the sow look like this servant, but he had a telling name:

Thomas Hogg.

God, I love history.

Take Me Back to Taos

A recent conversation turned to traveling, and destinations in the Southwest came up. I don’t recall if someone mentioned Arizona or New Mexico, but I quickly offered my opinion that Phoenix is a hellhole I could easily never visit again, and that one of my favorite places in the world is northern New Mexico, specifically Taos.

One of my tablemates had never heard of Taos, which I guess is not surprising if you’ve never been to the region. Home to barely 4,000 souls, it probably only registers for culture mavens, students of US history, and skiers.

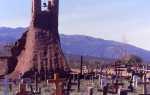

For most tourists, the main attraction is the Taos Pueblo, just a few miles out of town. Some times when I’m relaxing, I imagine taking that drive from the center, bearing right, heading past the tiny “casino,” and pulling into the parking lot. To your left is a cemetery and ruins of a church (more on that later), while the center is filled with the original adobe pueblo. Behind it is part of the Sangre de Christo Mountains and the unseen Blue Lake, a sacred site said to be the birthplace of the Taos Indians. To the right is another part of the pueblo. The pueblo’s claim to fame: It has been continuously inhabited for 900 or so years, longer than any other spot in the country. About 150 people live in there year round, eschewing electricity and other modern conveniences as they remain true to their culture. Other tribal members live near the pueblo and spend time there during the summer.

The people of Taos are sometimes called Pueblo Indians, along with the other Indians of the region. They trace their roots to the Anasazi and Mogollon of centuries past. The native New Mexicans speak three different but related languages; Taos and several other pueblos nearby use Tiwa. The Taos and tribes from the other pueblos nearby greeted the Spanish when they explored the region in 1540. Unfortunately for them, the Spanish were looking for more than just a hearty welcome. Gold topped the list, along with converts to Catholicism. Suffice to say, as in Florida and just about everywhere else the Spanish came ashore in North America, the visitors did not bode well for the Pueblo Indians.

The Spanish largely ignored New Mexico until 1598, when the first settlers trekked north from Mexico. Under the leadership of Juan de Onate, they subdued various Pueblo tribes. By 1680, the Indians were feeling less hospitable, and Taos and the other pueblos united in a successful, though short-lived, rebellion. The leader, a shaman named Popé, lived for a time in Taos. The people there had shown their resistance to foreign rule even earlier, killing a missionary decades before. But after the Spanish reconquest of northern New Mexico, the Taos and their neighbors remained under Spanish rule for almost 150 years. Only to see another bunch of white-skinned outsiders seize power during the Mexican War.

Among many US leaders of the 1840s, taking Mexican lands, especially the much-coveted California, was part of America’s grand “Manifest Destiny,” a mission from God much less entertaining than the one Blues Brothers undertook. In 1846, soon after the Mexican War began, US forces quickly took control of northern New Mexico. Charles Bent, an American trader who lived in Taos, was named the governor. Local Indians and Spanish New Mexicans joined forces to resist their new rulers, killing Bent and other Americans. The rebel leaders, along with civilians, holed up in the Taos Pueblo mission church, where a much-better armed American force carried out a retaliatory attack. The remains of the church and the graves nearby still remind the Taos of their introduction to US rule.

In later years, another American who lived in Taos, Kit Carson, did his part to endear the Americans to the Native Americans of the region. He carried out bloody attacks against the Navajo, as the US government tried to force them onto reservations. You don’t often hear as much about that as you do his exploits as a frontiersman. His house is in downtown Taos (such as it is) and serves as a museum.

New Mexicans, whether Spanish or Indian, were not too respected by the incoming Anglos. That’s one reason why it took so long for New Mexico to become a state, as American leaders doubted their ability to practice democracy. But finally, the territory joined the Union in 1912, and soon artists discovered the natural beauty of northern New Mexico. Socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan built a home in Taos and invited artists to work there. Georgia O’Keefe and Ansel Adams were just two who accepted the offer, drawn to the light and the mountains and allure of the high desert. D.H. Lawrence came too, and he later bought land outside Taos (of course O’Keefe became the most permanent transplant of all, settling down in not-too-distant Abiquiu).

Today Taos still has its cultural scene and a counterculture feel. The three influences – Pueblo, Spanish, and Anglo – live side-by-side, if not always comfortably. I’m drawn to the region because of that blending, because of the history, and because of the spiritual sense I feel as I look at the mountains or watch the sunset. After my first visit, travelers’ Stockholm syndrome took hold: I was ready to sell most of my possessions and move there. I didn’t, but I still think about it. In the meantime, I visit whenever money allows, And when I meet people who have never heard of Taos, I quickly tell them of all its splendors.

The Great Americans – Mostly

What do Matthew Maury, John Lothrop Motley, and William Morton have in common (besides last names that begin with “M”)?

They are all relatively unknown today, even to some history nerds. And they are all honored at the Hall of Fame for Great Americans in the Bronx.

What? Never heard of this august temple dedicated to true American heroes? Ok, so it’s not exactly Cooperstown or Canton. I had come across it before, doing research for one of my books. But as the New York Times recently reported, the hall has hit some tough times, largely ignored by tourists and its current host, Bronx Community College. But once the Hall of Fame, the first national hall in the country, was a big deal.

The hall was founded in 1900 by New York University with a $250,000 donation from philanthropist Helen Gould Shepard, daughter of infamous robber baron Jay Gould. Her gift stipulated that candidates had to be dead at least 10 years, which was later extended to 25. A college of 100 electors chose the first 50 inductees, with plans to single out other great Americans every five years. Busts of the members sit along a semi-circular colonnade that overlooks the Harlem River. In a democratic touch, any American could nominate someone for induction, as long as the candidate was a U.S. citizen. Nominees needed 60 votes to get in.

The hall was founded in 1900 by New York University with a $250,000 donation from philanthropist Helen Gould Shepard, daughter of infamous robber baron Jay Gould. Her gift stipulated that candidates had to be dead at least 10 years, which was later extended to 25. A college of 100 electors chose the first 50 inductees, with plans to single out other great Americans every five years. Busts of the members sit along a semi-circular colonnade that overlooks the Harlem River. In a democratic touch, any American could nominate someone for induction, as long as the candidate was a U.S. citizen. Nominees needed 60 votes to get in.

Sources agree that at one point, the hall was a popular tourist site. But after 1976, no more elections were held, and there was no money to erect plaques or busts for the last four of the hall’s 102 inductees. NYU sold the site in 1973, and as the NYT article says, the “busts tarnished, soot gathered, and the Hall of Fame slowly slipped into irrelevance.”

So who are some of the great Americans honored here? Not everyone is as obscure as the names I listed above, and plenty of the usual suspects got the nod. Among presidents, we have Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, both Adamses, Jackson, Lincoln, and Roosevelt. Military heroes include Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Ulysses S. Grant (surely he was not rewarded for his presidency, right?). For science and invention, there’s Edison, Agassiz, Morse, Westinghouse, and the Wright brothers. Artists of all stripes include Twain and his Hartford neighbor Stowe, Emerson, Thoreau, Whistler, Whitman, and Sousa. Other inductees come from the fields of medicine, law, education, and social reform.

And what about my less-well known trio above? I had never heard of the first two. Matthew Maury was a U.S. naval officer who became a well-regarded oceanographer. His knowledge of winds and currents helped American captains take the fastest routes across the oceans and earned him the nickname, “Pathfinder of the Seas.” When the Civil War began, he served as the South’s naval commander. He spent time in England, helping the South acquire new vessels.

Mystery Great American number two, John Lothrop Motley, was not as dynamic a chap. No, Motley was that most useless of all things in America, a historian (though he served briefly as a diplomat). The product of a fine Massachusetts family, Motley tried his hand at fiction, failed fairly miserably, then dedicated most of his adult life to the study of Dutch history, focusing on the rise of the republic after years of Spanish rule. Yes, the kind of work guaranteed to thrill 21st-century Americans.

And finally, William Thomas Green Morton, whose name I did know. Morton was a dentist, but not just any dentist. Morton, some folks believe, was the first to use ether to anesthetize a patient. In reality, the credit should go to Georgia surgeon Crawford Long, who gave ether to a patient several years before Morton. The dentist, however, wrote about his experiment while Long did not, ensuring Morton’s place in the Hall of Fame. Morton got the idea for using anesthetics after watching a failed experiment conducted by his former dental teacher, Horace Wells, who thought nitrous oxide could be useful as a painkiller. Wells was right, of course, but the patient he treated during his public experiment yelped in pain, due to faulty administration of the drug. Wells was discredited, leaving the path open for Morton to take credit for being the first to successfully use anesthesia (Long notwithstanding).

Perhaps Long should have Morton’s spot. Some say Morton was more interested in fame and money than medical breakthroughs, though he did treat many wounded soldiers during the Civil War. Wells, meanwhile, had a tragic end; his dogged attempts to end suffering during surgery led to experiments with chloroform and addiction to the drug. In a stupor, he threw acid on two prostitutes, was sent to prison, and killed himself. OK, so maybe not a candidate for the hall, though historians suggest he had higher moral character than his former pupil, Morton. Of course, plenty of great Americans would not make the best Sunday school teachers, hmm?

To see a list of the 102 inductees, go here. How many names do you recognize? (I knew 85, though I might not have been able to tell you why all of them were famous). You’ll also notice a contemporary complaint about the hall: few women and minorities. People calling to revitalize the hall hope to make new inductees more reflective of a diverse United States.

Naked Ambition

I was shocked, shocked, to see that there is public nudity at Yale. Imagine, acts of debauchery going on at one of our more august institutions of learning, a nurturer of our finest minds and most moral business and political leaders.

Right.

Actually, the nakedness wasn’t completely public; you had to know about the party where birthday suits were de rigueur. And apparently it was a chaste affair, despite all the flesh (though one guest was asked to go outside when he displayed a little genital exuberance).

I learned about the naked party in the Yale Daily News, which was referencing a blog from the Harvard Crimson. Evidently, some Harvard students down in New Haven for “the Game” were a bit surprised to come across a naked party – and the Elis’ blasé attitude toward the frolicking sans clothes.

No, there were no Ivy Leaguers nakedly parading through the streets of the Elm City that night – at least none that made the news. But the article got me thinking about going outside one’s own home without clothes. Not my own home, mind you; I have skinny-dipped or sunbathed au naturel exactly two times in my life, and odds are the count won’t be going higher. But what about throughout history; who were some of the folks who make a social statement with their fashionless statement?

We had the streaking craze, of course, about 35 years ago. And naturists, (the term preferred over nudists) have sunned and romped in the buff at their own enclaves for more than a century. Greek and Roman athletes competed nude, explaining why few women were allowed at the original Olympic Games. (The exceptions, says Tony Perrottet in his Naked Olympics: young single women, especially ones looking for husbands, and prostitutes. Ah, athletes and the ladies: some things never change…) A series of Christian sects I’d never heard of before practiced nudity as part of their beliefs. They included the Carpocratians, part of the Gnostic movement of the 2nd century, and the Marcosians, a slightly later group based in France. Rather than flaunting their nudity, they lived in isolated areas or behind stone walls, but just knowing they were there upset the Church powers-that-be.

The early Quakers gave us a more public display of religious nudity. (The Quakers? Yes, and you can read about my interest in the practice here.) They used biblical justification for their nakedness, which was a taunt at the ruling Puritans who scorned them: “’Go, and loose the sackcloth from your loins and take your sandals off your feet,’ and he [Isaiah] had done so, walking naked and barefoot.” Some modern Biblical scholars say, don’t take that literally, he wasn’t really naked. But the Quakers did take it literally, if only because they loved tweaking the Puritans.

During the last few years, public nudity made the news, thanks to Vermont. State statutes do not ban public nudity, so in 2007, some folks in Brattleboro, from teens to the elderly, decided to exercise their civic right to stroll through town in the buff. The town council then voted to temporarily prohibit public nudity. Thankfully, sanity triumphed and the ban was soon reversed. Would you really want to live in country where you can’t go to at least one town and proudly strut your stuff without rebuke? (Assuming your stuff is truly strut-worthy; the skinny excuse of a butt I carry around would definitely not past muster.)

I don’t have any profound summation on the pros and cons of public nudity. I guess seeing others’ naughty bits could get distracting (see the case of that poor Harvard undergrad above), though the folks who attended the Yale party said most eyes seemed to be conspicuously focused above the neck during conversations (dancing, however, was prohibited). I understand America’s puritanical streak (as the Quakers did), so I don’t expect an upswing, as it were, of naturism. But I also understand the appeal of being outside, under the sun, enjoying nature with nothing between us and our environment. With no one worried about how their clothes fit and if they’re the latest fashion. Going beyond the superficiality of looks and taking people for who they are, with no discrimination or sense of superiority. Just as all of today’s naked Yalies surely must do as they go on through life and enter the corridors of power.

Right?

Recent Comments